Holodomor Awareness Through Film, A Traveling Bus, And A Newly Uncovered Canadian Journalist

Feature Interview: film maker Andrew Tkach and lawyer Bohdan Onyshchuk talk to Bohdan Nahaylo about the Holodomor and more

Hello and welcome to this week’s Ukraine Calling programme. I’m Oksana Smerechuk for Hromadske Radio in Kyiv. We’ll have a roundup of the weekly news for you, some culture, and some music. We’re bringing you a feature interview with Andrew Tkach and Bohdan Onyshchuk talking about a new documentary film on the Holodomor and about a Canadian, Rhea Clyman, who was one of the first to report on it. But first the news.

Feature Interview: film maker Andrew Tkach and lawyer Bohdan Onyshchuk talk to Bohdan Nahaylo about the Holodomor and more

NEWS

CULTURE and MUSIC

LOOKING FORWARD

Hromadske Radio is independently funded. We are appealing for funds through a crowd funding initiative. Should you feel inclined to donate, you can do so here.

Feature Interview: film maker Andrew Tkach and lawyer Bohdan Onyshchuk talk to Bohdan Nahaylo about the Holodomor and more

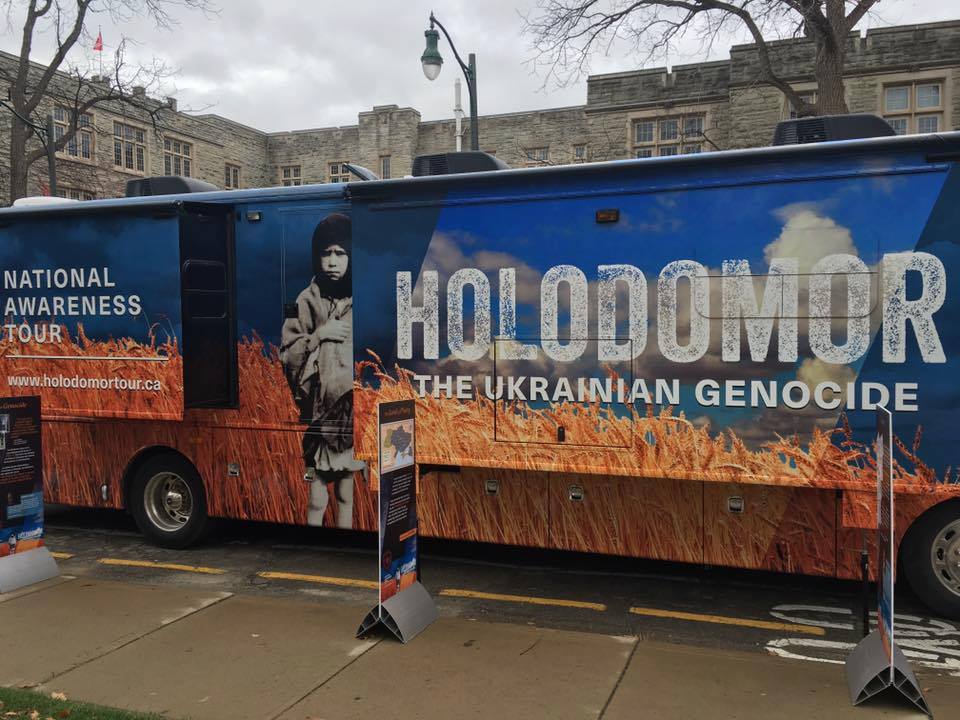

Nahaylo: Welcome to our weekly in-depth discussion. We have been commemorating the latest anniversary of Holodomor, the genocide through an artificial man-made famine – Stalin’s famine, in Ukraine. I am very fortunate and privileged to have two people with me today who have really made a great effort and contribution in getting this theme known not only in Ukraine but also in the outside world. First, I have Bohdan Onyschuk, a Canadian lawyer -he will tell us a little bit more about himself – a veteran in this sphere, who is also Chairman of the Holodomor National Awareness Tour. How would I describe you?

Onyschuk: Chair of Holodomor National Awareness Tour.

Nahaylo: So here is Bohdan Onyschuk, who is Chair of Holodomor National Awareness Tour and has been responsible for various documentaries, films and publications. More about this later. Also here, Andrew Tkach, a veteran filmmaker, a film director, a long standing producer of Christiane Amanpour of CNN.

Tkach: I produced her long-form documentaries for 13 years.

Nahaylo: And recently you also produced a film on Maidan. We will be talking about the latest film on Holodomor, which has a new novel angle to it. But more on that when we will get into discussion. Bohdan , you are a lawyer by background?

Onyschuk: Yes.

Nahaylo: How did you get involved in the theme of Holodomor many years ago, not just now?

Onyscuk: Having grown up as a Canadian Ukrainian and having emigrated to Canada as a small baby from Lviv with my parents and my brother, the rest of it, I think , is pretty clear. We tried to carry on, not just the tradition but keep the Ukrainian language and history alive. I got immediately involved with Ukrainian community organizations and through that, all of the main efforts in terms of what the big issues are, and particularly, in this case, the Holodomor, which was denied up until 1991.

Nahaylo: Tell us a little bit more about the early days about the very first documentary that was made by the Canadian Ukrainian community.

Onyschuk: That is why we set up the Ukrainian Canadian Documentation Centre in Toronto in 1981. We were coming up to the 50th anniversary of Holodomor commemoration. At that point the Soviet Union was still denying that any famine had existed – never mind genocide – and of course the Ukrainian Canadian community had carried the story with them all the way from Europe, which was considering it as a genocide. It was a huge famine. So we decided that that was a time to try and do a major documentary. The Ukrainian Canadian Documentation Centre , UCDC, was incorporated. I was one of the founders of UCDC and was its Vice-Chair for 15 years.

Nahaylo: This initiative was supported by the community, by private donors?

Onyschuk: It was both. It was based on our heavy hitters from the main organizations in Canada.

Nahaylo: does it coincide with what the Ukrainian Harvard Research Institute was doing, with James Mace and Robert Conquest?

Onyschuk: James Mace actually came a little bit later. But yes, absolutely, it did. And we were very close with James. He was a terrific guy. And we found Robert Conquest in England. His book is called Harvest of Sorrow because it was a take off on our film which came out three years before the Harvest of Despair and which won seven documentary golds. And it was through Malcolm Muggeridge that we got to Robert Conquest, and of course he did one of the major works on the Soviet Union and Stalinism.

Nahaylo: I had a privilege to know both Robert Conquest and Malcom Muggeridge, and James as a very good friend, Bu but the challenge then was how to get awareness of what had happened in Ukraine in 1932-33 to the outside world, to a sceptical world, to a leftist audience, which very often could not accept that this did happen and believed in technical issues such as the climate and failure of the harvest . Jumping ahead, have we made much progress in the last 30 years in getting this across?

Onyschuk: I think absolutely. Harvest of Despair was a great start because, being a lawyer and a lawyer on the original committee of UCDC , I knew we needed hard facts. And because we were coming to the 50th anniversary we were also coming to 50 years in diplomatic terms to the release of archives. So we new there would be Italian archives released because they had a consulate in Kharkiv. We knew German archives would be released, and the British archives from Moscow were being released. So we focused on those, and we found ae treasure trove.

Nahaylo: I know. But the challenge was again to interest those who were not Ukrainians in it. And I will turn now to Andrew. Andrew, you come from this filmmaking background. What got you interested in this later project? Could introduce your new film and tell us what is the novelty about it? It was screened in the Ukrianian Parliament, Verkhovna Rada, today.

Tkach: I have produced a film in Ukraine just right after Maidan with a local filmmaking group here – Babylon13. I think it came to the attention of the Canadian Ukrainian Foundation. That is how they knew about me. They came to me – and I am working n Africa now, in Kenya- and said: “We have this project and we would like you to be one of the competitors for it. Can you take a look at it?” And I was quite sceptical at first because I am a filmmaker dealing with a real life, not past life, especially with people who were unknown, no material on them, no documentary footage. They sent me the articles that Jars Balan had found, and I read them, and I found her (Rhea Clyman) voice to be interesting. In other words, for me as a filmmaker, what is interesting is the biggest story but also

Nahaylo: Jars Balan is a Ukrainian scholar based in Edmonton. What did he discover? What was interesting about this?

Tkach: There were two dozen articles published at the time and written by her, and she was very descriptive.

Nahaylo: Could you introduce her? Who is she?

Tkach: Rhea Clyman was a 20-something-year-old journalist who went to Moscow, pretty much penniless. We when she came to Moscow she slept in somebody’s bathtub that she met on the train. She was an adventurer, very much a leftist.

Nahaylo: a Canadian-Jewish woman?

Tkach: Yes. Who came here like many people at that period with an idea they are about to witness the new society being born.

Nahaylo: Like Malcom Muggeridge from Britain.

Tkach: Yes. But unlike the rest of people, because she was poor and was not supported by The New York Times or anybody else, she was a freelancer. She got her room in a komunalka, a common apartment, and learned Russian very quickly. And probably lived like everybody else, not much better. We also know that her boyfriend was arrested for currency speculation and sent to the Artic, to Siberia. So that is why she went up there.

Nahaylo: But is she a subject of the film on Holodomor?

Tkach: Because one of the great coincidences of her carreer is that after they (secret service) discovered that she had written about the Stalin penal labour camps, they were about to kick her out. And somehow she convinced two American women to show up in Moscow in a car, and amidst rumours that a tremendous famine was going on, like a good journalist she convinced them to get in a car and drive through the famine zone.

Nahaylo: But this is also beacuse exceptional because she was working, Bohdane, as an assistant to…

Onyshchuk: —to Walter Duranty. I was just going to add that in, I think Andrew just skipped that part. When she came back from the tundra, she spent eight months working as the assistant to Walter Duranty.

Nahaylo: And who was Walter Duranty?

Onyshchuk: Well Walter Duranty was the ‘big liar’ who basically promoted the Soviet lie. Working for The New York Times, he won the Pulitzer Prize and was the correspondent that everybody kowtowed to in Moscow and back in North America, but who fed the big lie.

Nahaylo: He was a fibber.

Onyshchuk: Was a fibber, big time! But to her credit, and to answer your question to Andrew, she was the kind of journalist—which is why we wanted to make this film about her—who wanted to get at the truth. She saw that Duranty was lying and she saw that the Soviet Union leadership was lying. They were calling it Valhalla, the next millennium, the utopia, but all she saw was bread lines and food lines in the city in Moscow, and outside of the city the place was collapsing. It was certainly not anything approaching any utopia.

Nahaylo: So she — despite being an invalid herself as Andrew has told me she only had one leg due to an accident in childhood — courageously with two other women, driving across the Soviet Union south to Georgia through Ukraine, through the famine-stricken regions, through the Caucases, and ending up in Georgia, and witnessing these horrible scenes.

Onyshchuk: Right.

Nahaylo: And have we found much that adds to the story of the Holodomor?

Onyshchuk: Oh a lot! First of all, she was the first journalist to write about it. She was there first before Jones, before Muggeridge—not by a lot but by two-three months in terms of Jones, and about five-six months in terms of Muggeridge. And she wrote about it. But she wanted to see for herself what the situation was in Ukraine — which was then part of the Soviet Union of course— and to be able to see whether what everyone was talking about in the back rooms in Moscow was in fact true, which was that there was a famine going on, but nobody could any visas to go into the country. So she did it with a couple of American heiresses who had this fabulous car and two bottles of champagne, and away they went!

Nahaylo: So they made this trip: she gets arrested, the films tells us, when they arrive in Tbilisi, she’s kicked out of the Soviet Union, and writes these incredible articles for a London newspaper, and for a Toronto newspaper.

Tkach: What’s interesting actually is that there were no restrictions on journalists before she was kicked out. It’s only in reaction to her reporting, and one or two other reports that there is documentation, that Stalin says we cannot have more of this. S she went there without a minder, and because she spoke Russian she could operate freely in the country.

Nahaylo: What makes the film so interesting as well is that she, being of Jewish origin, reports about the famine in Ukraine and, after she gets back, instead of being totally disillusioned and cynical, she publishes these articles and then applies for a job as a correspondent in Nazi Germany and begins reporting on the Nazis. This is a remarkable story of a woman that reported on two horrendous crimes against humanity. The Holocaust hadn’t happened in the 1930’s, but the Nazis were well on their way to showing their colours.

Tkach: She’s quite cynical when she talks about it. She says, “I went to Canada and was given non-paying jobs with women’s gloves making speeches.” She’s not somebody that had money ,so she needed to go where the action was, she says, and the action was Nazi Germany. It’s very much a freelancer’s mentality, which I understand totally having worked freelance for five years. So what was also interesting when I read about the Nazi period (we didn’t go into it in detail in the film) was that she went to the border of Austria on a hunch before Hitler invaded Austria and did it all through personal connections with various SS officers she had met. She even jokes in the book that she is meeting people who claim they can smell somebody of Jewish origin — well clearly they couldn’t! She was an enterprising, courageous person.

Nahaylo: Amazing story. It would be of course remarkable if we managed to find in her writings, or in her diaries, or any papers: did she make any comparisons in the 1930s between what she had witnessed in the totalitarian nature of the Soviet society and the growing totalitarian nature of the Nazi society?

Tkach: She did.

Onyshcuk: We’re looking for her diaries and basically her notebooks. Jars Balan who did the script for us, is a historian and an academic at the University of Alberta, and he is into this big time. She unfortunately, when she got back after the war, sort of got lost and passed away in White Plains, New York, many years later.

Nahaylo: An unsung heroine in many ways.

Tkach: An unsung heroine – absolutely right. But we’re trying to find them because that would be a very interesting connection.

Nahaylo: Rhea Clyman – the subject of a new film which is very aptly titled: Hunger for Truth. Andrew, you’re the producer and director of this film, Was it a difficult task to put all of this together and find a formula to make it work? Because what is also very interesting to those of you who have not seen the film yet is that it relates what happened in the 1930s in the Holodomor to what’s happening today in Ukraine in the war with Russia, and particularly the situation in the Donbas.

Tkach: Yes. I mean that was a difficult decision to make. I always felt, having worked in Ukraine during the Maidan, that there were so many tragedies in the 20th century that people’s eyes glaze over if you talk about another tragedy. It doesn’t have the same kind of relevance if you cannot relate it to today’s conflicts. So in terms of the script, basically once I received the outline from Jars (that was a two page outline with the 24 articles), I just locked myself up one weekend and wrote the Rhea story totally from her own words. The film does not have any narration. It’s strictly her own words. The more complicated story was: how do we integrate what is happening today — because disinformation is very much in the toolbox of demagogues now — to what was happening then. So the key was to try to relate those two. One could easily have picked a journalist working today and it would have made logical sense, but from a dramatical sense I think it was better to take somebody who was a victim of the current conflict, and disinformation is the backstory. But people in effect always relate better to personalities on screen than they do to abstract ideas.

Nahaylo: Right. Well I hope we’ve wetted the appetite of those listening. If somebody wants to see this film in the future, how would they go about it?

Onyshchuk: Well get in touch with us. We’ve put the film out for festivals and so there’s only a premiere of it, because of the festivals we’re looking at, and you can’t have a public showing or put it out to the mainstream theatres until after the festivals. So that’s going to happen in the early spring. In the meantime we’re certainly available for universities, for libraries, for documentation centers, we’re making the DVD, which is done in 4K. One of the things I’ve got to add is that Andrew and the team at Babylon 13 were phenomenal in terms of getting original archival footage from the time of, not just Moscow and Ukraine, but also Tbilisi. Every aspect of it is historic and that was a requirement from us if we could do it, both with the Dovzhenko Centre and the stuff that’s become available and open, it’s an absolute knock out. So you’ll have to wait until the spring for public release.

Nahaylo: Because time is running out: We seem, as Ukrainians and people concerned about our past, to be in a much better position today. We’ve seen the publication of Anne Applebaum’s book Red Famine, we’ve seen the works by Timothy Snyder putting things in a broader geopolitical and temporal context. So what are the major tasks and priorities that await us? One of the questions that was asked today by the parliamentarians was: how should we go about celebrating the 85th anniversary next year of the Holodomor? Is the task now to try and get it recognized as genocide by as many countries as possible? Or, what? What would you say are the priorities now?

Onyschuk: I think the recognition is half-way done. Seventeen of the major Western democracies have recognized the Holodomor as a genocide, including Canada. Canada was about the fourth, I think. But work is not finished it that regard. I think the next important priority, which was also discussed today, was the museum here in Kyiv. I mean you have got the commemoration of Holodomor with a candle, overlooking the Dnipro river, but phase two is the museum itself. And I think from what I have heard is that Verkhovna Rada and the Government would like to see at least half of the museum being built before the end of 2018.

Tkach: From my point of view, I am not a propagandist, I am a storyteller – that is what a journalist should be. When people, ask why do not we have a particularly message in the film, it is almost irrelevant to me. I mean the film is about a person…

Onyschuk: That is, a documentary…

Tkach: The story holds up dramatically, has to hold up factually that I am not here to make the definitive treatment of the Holodomor, you know.

Nahaylo: Okay, well look, we should mention while we are speaking about what Canadian Ukrainians have been doing, American Ukrainians and others: I want to just pay tribute to the constant ongoing work, serious work, that has been done by Ukrainian historians. We have got here, in the studio (she is not taking part, she is a passive observer) Liudmyla Hrynevych. I have got her big tome here chronicling the collectivization campaign and the Holodomor in Ukraine, 1927 – 33. The volume two, but just book one. I mean – a huge undertaking. So clearly, you know, in the last 25-26 years, very substantial work has been done by historians in Ukraine to fill this blank spot, or should we say, suppressed spot. Any comments about that? Are you working closely with historians in Ukraine?

Onyschuk: We are. I mean HREC (Holodomor Research and Education Centre) and Liudmyla Hrynevych is part of the Holodomor National Awareness Tour. Her bosses in Canada, which is where HREC is founded, are part of our consortium, and we rely on them and rely on the UCDC. But there is so much research out there, and there is still a lot to be done, that has to be done here because it happened here. You have got great historians here in Ukraine, and you have got the archives here. There are certain archives that are out in the West, but basically there is a lot of research that can happen and books that need to be written.

Nahaylo: Okay Bohdan, I will give the final word to Andrew. Andrew, you made the effort of trying to link up the story of the Holodomor to the current situation and its challenges. So, for you personally, what are the lessons we draw from that terrible experience in our history?

Tkach: I think that main lesson is that disinformation kills. That just like in Stalin’s time, when there was denial of this massive tragedy, currently in the conflict with Russia there is an absolute denial of the reality that there is an occupation forces, and people are dying on a daily basis as well. That is very clearly brought out, when we had Liudmyla Hrynevych, when she talked about how during the Holodomor and the Holocaust first you had to actually debase the humanity of your victims. And the same thing you could say happens during disinformation today. When Russian media talk about Ukrainians they refer to them in the most extreme language, and that allows people to go and volunteer for the Donbas effort and kill people. So, it is not an abstract idea, it is something that causes real damage and my goal as a journalist is just to point to the truth as much as I can.

Nahaylo: Well, thank you very much! This has been a fascinating discussion. I want to thank Andrew. You have just heard Andrew Tkach who is, as I have introduced him, a filmmaker, film producer, now becoming a historian of sorts, a thinker on this topics. I also want to thank Bohdan Onyschuk, an eminent Canadian-Ukrainian lawyer, community activist, and one of the driving forces of several decades in getting the Holodomor message across and the story on. I thank you, gentlemen.

NEWS

Saakashvili

There were some dramatic scenes in Kyiv this week as former Odesa region governor Mikheil Saakashvili was arrested, only to be freed by determined throngs of supporters. Police conducted a search of Saakashvili’s apartment early Tuesday morning, 5th of December, leading the politician to try to flee via the roof of the building. He was detained and put in an SBU van, but the crowds of his supporters clashed with police, and helped him to escape the van. He then continued with the crowds on to the tent city outside the Verkhovna Rada, where he led rallies, vowing to fight corruption and calling for removal of the government in power and for impeachment.

That same day, Ukraine’s Prosecutor General, Yuri Lutsenko, held a press briefing, where he claimed that the government had evidence that Mikheil Saakashvili was being financed by persons linked to ex-President Victor Yanukovych. He named Ukrainian oligarch Serhiy Kurchenko, an associate of Yanukovych who had fled to Russia, as allegedly financing Saakashvil in order to stir up protests aimed at seizing power in Ukraine. This would assist Yanukovych and associates to resume control over the assets they had had in Ukraine.

Saakashvili has called the charges and the evidence against him “fake.” President Poroshenko commented to say that Saakashvili’s actions were aimed at destabilizing the situation in the country.

[Note from the Edtior. As this publication was ready, Ukrainian officials and Saakashvili supporters reported that Mr. Saakashvili was arrested for the second time. He was brought to SBU detention facility in Kyiv].

National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine

This week, Ukrainian activists and reformist lawmakers worked together to save NABU, the National Anti-Corruption Bureau, from what seemed to be a government attempt to disarm anti-corruption reform.

The Verkhovna Rada had registered a bill, drafted by the Bloc Petro Poroshenko Party and Arseniy Yatseniuk’s party, which would give the Parliament and the President the right to dismiss the director of NABU. International financial institutions and other Western partners expressed concern, that this move would be rolling back reforms.

The bill was to be put to the vote in Parliament on December the 7th, but activists and reformist legislators mobilized through social networks and the bill was removed from the agenda.

Later in the day, however, there was a different setback, when, in a separate vote, the Verkhovna Rada voted to dismiss the head of the Parliamentary Anti-Corruption Committee, Yehor Sobolyev.

In the meantime, President Poroshenko urged the Ukrainian Parliament to expedite the creation of an Anti-Corruption Court, and proposed to table the draft law himself.

Law on Domestic Violence

This week the Verkhovna Rada passed a law on Domestic Violence, which makes it punishable now under Ukrainian criminal law, thus making offenders liable to more serious consequences. The law will serve to protect the victims of physical, psychological or economic violence in the family. According to data provided by UNIAN, some 165,000 women report domestic violence annually, although the real figures are estimated to be 5 times higher. The new legislation makes provisions for financing of women’s shelters, creation of rehab programs for victims and psychological and legal support for victims.

The War

According to the official data, announced by the Ukrainian President Poroshenko on December 7th, since the beginning of the anti-terrorist operation in Eastern Ukraine, Ukrainian forces have lost more than 2,750 people. During the first week of December the situation on the frontline remained unchanged. Ukrainian officials reported constant shelling of Ukrainian positions by pro-Russian forces, which usually intensify during the night. On December 2, pro-Russian forces reportedly shelled residential areas of the settlements of Vodiane, Avdiivka, Verkhnio-toretske (Donetsk region), and there was 1 civilian casualty. On December 6, pro-Russian forces shelled Ukrainian positions near the settlement of Novoselivka (Donetsk region) with mortars. Officials are reporting that one of the mines that was used against the Ukrainian army, contained phosphorus. Over the first week of December, Ukrainian army lost 1 soldier, KIA, and 12 wounded.

Crimea

Ukrainian political prisoner, Viktor Balukh, has been placed under house arrest. He had been previously held in pre-trial detention for a year. Russia’s FSB had detained him exactly a year ago on fabricated charges of allegedly holding stockpiles of bullets and explosives. The case has been widely criticized by human rights groups, who say that the explosives were planted. And Viktor Balukh maintains that he has been detained because of his pro-Ukrainian stance.

CULTURE

A new exhibit just opened in Kyiv’s Mystets’kyi Arsenal. It’s called Boychukism: A Project about Great Style. Mykhailo Boychuk was an early 20th century painter who transformed Ukrainian art. His work caused a stir in Paris’ Salon des Independants in 1910. In 1917 he was one of the founders of Ukraine’s Art Academy, and had a huge impact on the art scene before being purged in the 1930s. The exhibit curators are Olga Melnik, Victoria Velichko, Igor Oksametny. This is how they describe it: “This is a project about dreamers who wanted to change the world. This project is about the reformers of art, who abandoned the traditional format. This project is about the creators of Utopia, who themselves became its victims …” The exhibit is on until 28 January 2017. We’ll post a link to it on our website.

MUSIC

The L’viv group Sixth Sense (Шосте Чуття) recently released a new album. One of the songs I liked best was their contemporary rendition of the Ukrainian folk song ‘Як Приїхав,’ which means ‘When I Got There.’ Enjoy!

LOOKING FORWARD

Next week Bohdan Nahaylo will be hosting the show and we’ll be back with even more news, culture and music, so tune in again for a new edition of Ukraine Calling. We would be happy to receive any feedback from you. You can write to us at: [email protected]. This is Oksana Smerechuk in Kyiv. Thanks so much for listening.