Helping civilians in illegal detention and their families — NGO «Egida-Zaporizhzhia»

Antonina Shostak, a lawyer with the NGO “Egida-Zaporizhzhia,” discusses organizing assistance for civilians in illegal detention and their families in Zaporizhzhia Region.

About the organization

Antonina Shostak: «Egida-Zaporizhzhia» is a project aimed at supporting civilians in illegal detention and their families. Unfortunately, we also receive numerous inquiries from families of victims. Our efforts extend beyond legal support; our lawyers accompany these individuals in court proceedings and prepare procedural documents. In the two months since the project’s launch, we have submitted approximately 80 requests for information.

Furthermore, we offer psychological support by hosting support groups for mothers and wives of the deceased and missing persons. Additionally, we provide social support for issues that extend beyond legal or psychological realms. These may include tasks like applying for a survivor’s pension or obtaining humanitarian aid. We can connect individuals with partner organizations operating in the Zaporizhzhia Region.

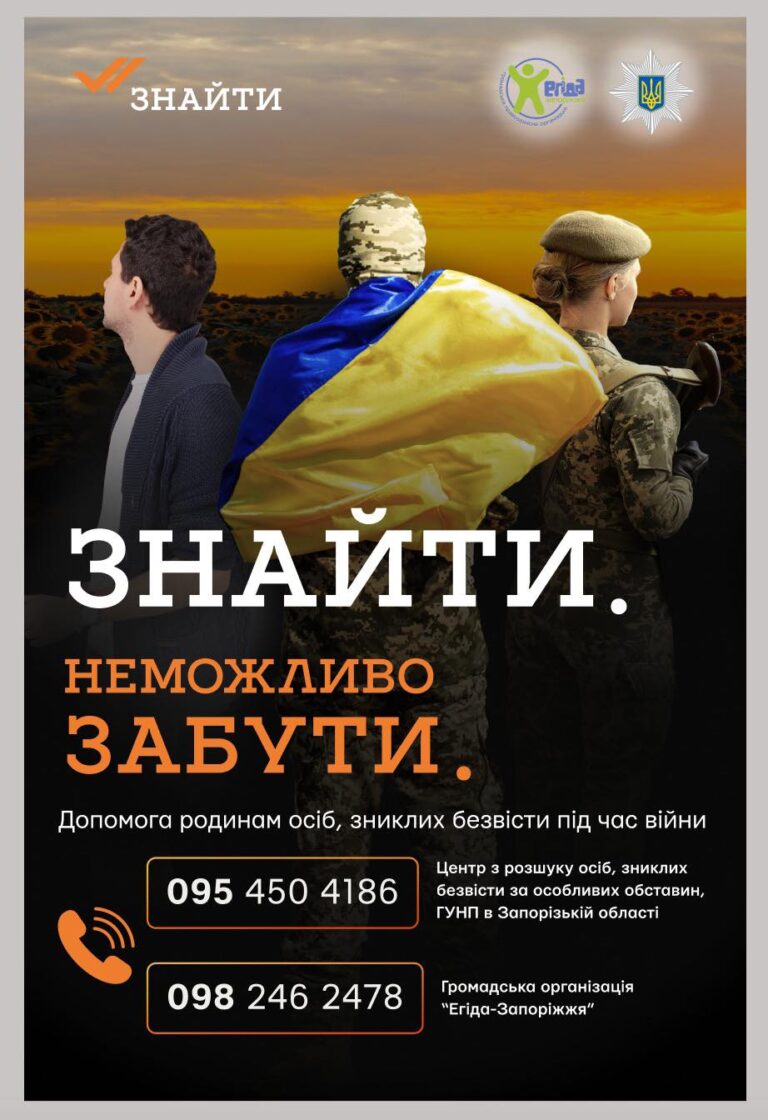

Of course, a significant aspect of this project is the extensive information campaign conducted in collaboration with the Main Department of the National Police in Zaporizhzhia Region. Presently, there exists a unique center for missing persons under special circumstances in Zaporizhzhia. What makes it distinctive? It’s because the center is immediately staffed by investigators, with a representative from the Department for Missing Persons of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, as well as representatives from our organization.

The «single window» principle ensures that all specialists are centralized in one location. Additionally, there is a small DNA laboratory available, which streamlines the process for individuals, eliminating the need to navigate multiple agencies or search for information independently. This setup enables individuals to access all necessary services and information concerning their relatives efficiently.

Read also: The «Chameleon» — a course about avoiding captivity and the psychology of survival in captivity

Scope of assistance

Antonina Shostak: The issue our organization addresses is so deeply impactful that our focus lies not on resources, but on providing assistance. Our case manager, who handles incoming calls, effectively allocates them to either a lawyer, a psychologist, or a representative of the ombudsman. This approach aims not to overwhelm, but to ensure each individual receives the necessary attention and support.

If a person has inquiries regarding an ongoing criminal proceeding, we prioritize direct communication with investigators to avoid queues. Additionally, the representative of the Commissioner for Missing Persons offers advice in an official capacity. We provide separate rooms where a psychologist assists families, and sometimes even law enforcement officers, particularly in addressing non-standard questions or delivering negative information to relatives.

We’ve forged strong partnerships within the communities. Zaporizhzhia stands out for hosting communities from all temporarily occupied territories, and community leaders demonstrate remarkable openness. To ensure inclusivity, we conduct on-site consultations as necessary, particularly for residents in remote villages. Our goal is to reach every corner of the region, making our services accessible and ensuring widespread awareness.

Naturally, the nature of requests varies widely. In many instances, individuals, feeling desperate, seek assistance from the relevant structures of the aggressor state. Numerous inquiries also surface concerning information hygiene and security. Misinformation circulating on social media, particularly about specific individuals, is a common issue we encounter.

In reality, with proper organization, queues can be avoided entirely. Each individual is provided with a dedicated consultation lasting between 30 minutes to one hour. It’s crucial for people to express themselves freely. We often dedicate substantial time to psychological stabilization as the situations we encounter vary greatly. We’ve witnessed the invaluable impact of psychologists’ work; they’ve successfully normalized the situations and behaviors of individuals, enabling them to articulate their concerns more clearly after calming down.

Read also: 108 days in Olenivka and no compensation for captivity from the state

Algorithm for confirming the status of a civilian hostage

Antonina Shostak: Concerning civilians who have been taken hostage or whose freedom has been restricted by Russian occupiers, several challenges arise. Firstly, when an individual is taken hostage, their relatives, friends, or acquaintances typically notify relevant institutions. In the Zaporizhzhia Region, there exists a hotline managed by the Zaporizhzhia Regional Military Administration, which citizens can contact. Information provided is recorded and relayed daily to the National Information Bureau.

The most recent individual who reached out to us had been held in illegal detention for approximately 45 days. Our assistance with him followed this algorithm:

There was a scenario where his capture was reported by individuals unknown to him, described as neighbors. Upon checking the registry, it was noted that the informant was listed as a «neighbor», despite not being related to him. This neighbor reported the incident to the military administration hotline, which then forwarded the information to the NIB (National Information Bureau). Consequently, the neighbor was identified as the informant across all records. When we contacted the NIB, we confirmed the presence of this information regarding the individual. This discovery proved highly valuable. Additionally, we came across several publications on Russian Telegram channels, serving as significant evidence supporting his status as a hostage.

If an individual has already been released and there is no information about their detention, a specific algorithm exists. The initial step involves reporting to the NIB that they were illegally detained from a particular date. It is preferable to do so through an official statement rather than by phone. Alternatively, contacting the hotline of the Zaporizhzhia Regional Military Administration is recommended. Moving forward, if an individual, for instance, crossed the border, certain documents are necessary. In my experience, there have been individuals who provided filtration certificates issued by the occupation authorities, which serves as a minimum requirement. I advise them to retain these certificates as they serve as documentation confirming the circumstances.

Next, it is imperative to initiate a criminal case. The Security Service of Ukraine handles cases involving civilian hostages. Therefore, an individual who has been held hostage or directly by the Russian occupiers should reach out to the nearest SBU office. The criminal proceedings should be opened under Article 438 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. It’s crucial to emphasize that it is specifically Article 438. Obtain an extract from the Unified Register of Pre-trial Investigations and secure a resolution for recognition as a victim. During the process, explain to the investigator the necessity of utilizing this document and request the interrogation report. However, before proceeding, draft a statement indicating the individual’s request for permission to partially disclose the secrecy of the pre-trial investigation in order to submit the interrogation report to the Ministry of Reintegration of Ukraine.

Next, if individuals who were in the temporarily occupied territory were detained while carrying out their work duties, the responsibility of managers is significant. If managers are aware that their employees do not report to work in that territory but have no information regarding their whereabouts, they should document these circumstances. In cases where there is information that a person has been detained, specific regulations exist, which unfortunately are often overlooked by the heads of Ukrainian enterprises. For instance, the accident manual explicitly outlines procedures for abduction or disappearance cases.

Regardless of the current situation in Ukraine, it is imperative to establish a commission tasked with conducting an official investigation, drafting an accident report, and officially recording it. This will serve as another document confirming the circumstances.

Information provided by the Human Rights Ombudsman can also serve as confirmation, especially if relatives or friends have lodged an application. Additionally, information from the International Red Cross may be available.

I’d like to emphasize that information posted on social media by concerned citizens can also be valuable. While we acknowledge that relying solely on such sources may not always be entirely accurate and could potentially be harmful, in this context, screenshots and video messages can serve as additional evidence confirming that the person was held captive.

When these documents are presented in their entirety, they will consistently validate that this is not a fabricated account. They will demonstrate that the person is not taking any unjustified actions to obtain funds from the state, as any granted status entails certain payments.

If a person was exploited while being held hostage, such as being subjected to forced labor, they can concurrently apply for the status of a victim of human trafficking or forced labor. It’s important to note that this status is granted separately.

Hostages are often tasked with digging trenches and engaging in strenuous labor, while women may be assigned duties such as cleaning houses and cooking. Hearing about these circumstances can be incredulous, making it difficult to believe that such situations occur in the modern world.

There are individuals who willingly engage in such situations, but there are also those who endure immense hardships. They face both psychological and physical pressure, with their families often being targeted as well. As a result, these individuals may feel compelled to accept proposals that, regrettably, are deemed acts of treason and collaboration according to our legislation.

Read also: «As long as there is no mechanism for the return of civilian prisoners, people will continue to die»

On distrust in state institutions

Antonina Shostak: The category of civilians doesn’t appeal much these days. Everyone fears that this information could harm their relatives who are still in the occupied territories, which prevents our citizens from receiving the benefits and statuses from the state.

There is a significant degree of distrust, particularly regarding open criminal proceedings. People believe that all information is being transferred to the other side.

Sometimes this information is transmitted unconsciously. I often cite an example that occurred with a civilian hostage who came to the prosecutor’s office for interrogation. There were two prosecutors in the room: one was interrogating her, while the other was simply working. In our office, there are several specialists working simultaneously. After she left, she promptly received a call from the temporarily occupied territory, informing her that she had been in contact with law enforcement.

As it turned out, the second prosecutor who was in the room inadvertently shared information about the individual who came for interrogation with one of his relatives. Certain regions are very small, a lot of names are known. This prosecutor didn’t consider the implications when they unknowingly disclosed details to a family member. The person who had been interrogated was understandably shocked. Upon analyzing the situation, we offered our apologies. Fortunately, there were no consequences.

Professionals working with this category of individuals should comprehend the significance of confidentiality. Even a seemingly minor information leak, which the person may not have intended to disclose, can have a profound psychological impact on those affected. They harbor a deep-seated distrust of the authorities, believing that any information they provide will inevitably be shared with the opposing side, potentially endangering their relatives.

Read also: «We need help with publicity» — sister of Oleksiy Kyrychenko, civilian hostage held by the Russians

In times of war, the program «Free our relatives» tells the stories of people, cities, villages, and entire regions that have been captured by Russian invaders. We discuss the war crimes committed by the Kremlin and its troops against the Ukrainian people.

The program is hosted by Ihor Kotelyanets and Anastasia Bagalika.

This publication is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in the framework of the Human Rights in Action Program implemented by Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union. Opinions, conclusions and recommendations presented in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, the United States Government. The contents are the responsibility of the authors.

USAID is the world’s premier international development agency and a catalytic actor driving development results. USAID’s work demonstrates American generosity, and promotes a path to recipient self-reliance and resilience, and advances U.S. national security and economic prosperity. USAID has partnered with Ukraine since 1992, providing more than $9 billion in assistance. USAID’s current strategic priorities include strengthening democracy and good governance, promoting economic development and energy security, improving health care systems, and mitigating the effects of the conflict in the east.

For additional information about USAID in Ukraine, please call USAID’s Development Outreach and Communications Office at: +38 (044) 521-5753. You may also visit our website: http://www.usaid.gov/ukraine or our Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/USAIDUkraine.